The impetus for the Eiffel Tower and the speed it was constructed was in preparation for hosting the World Fair of 1899. These world fairs or expositions or great exhibitions were the brainchild of Queen Victoria’s husband. The concept was to focus on trade, advancements in architecture, science and technology, and present any new inventions.

In 1901 the international exhibition was to take place in Glasgow, Scotland. The exhibition was on 73 acres of land at Kelvingrove Park. The structures on the sprawling site included a new Art Museum, an Eastern Palace, buildings for the various displays, a grand concert hall that could seat 3,000, cafes and restaurants, and various foreign pavilions.

The exhibition aimed to showcase Glasgow's progress in science, industry, and art. The organizers wanted the world to come and see Glasgow but also offered exhibits to Japan, France, Canada and Russia so that those attending could see other parts of the world.

These international pavilions included a model farm with a working dairy, windmill, and Russian village. Gondolas and Gondoliers were brought from Venice, offering rides along the River Kelvin that passes through Kelvingrove park. The Canadian pavilion was the most popular attraction with its water chute. Patrons could ride on a flat-bottomed boat that plunged into the river.

The exhibition opened on May 2, 1901, and ran for six months, closing on November 9, 1901, attracting over 11 million visitors, including Karl Creelman.

In a letter from Karl to the Truro News dated August 9, 1901, he writes:

“I went [...] and over to Glasgow where the exhibition was absorbing all the people’s attention and spare time. Of course, being in the city I could not very well help going to see the sights at the big show and indeed it was worth going to see - it wasn’t half bad at all. Some of the exhibits looked really well. The Japanese had a building all them themselves, a regular tu’pence’ha’penny toy shop, stocked with ashtrays and roosters with wire legs. It would be an exceedingly inquisitive person that would take more than ten minutes to go through their show.

In the main building were fine exhibits from Western Australia and Rhodesia (that is as far as they went, and Queensland has some fine samples of gold and rubies.)

Canada exhibits occupied considerable space, besides the building of their own outside. Canada has a good show - gold from Klondike, coal from Cape Breton from the extreme west of the Dominion and from the extreme east, with fruit, timber, grain, and a general assortment of all kinds of minerals from all parts of the country. Our exhibit somewhat resembles Russia, in the line of woods and grains. …In the Canadian department were dozens upon dozens of jars containing preserved fruits. The Indian canoes were much admired by the visitors and more than once I heard people say, “Well, I believe those Canadians have the best show ____”.

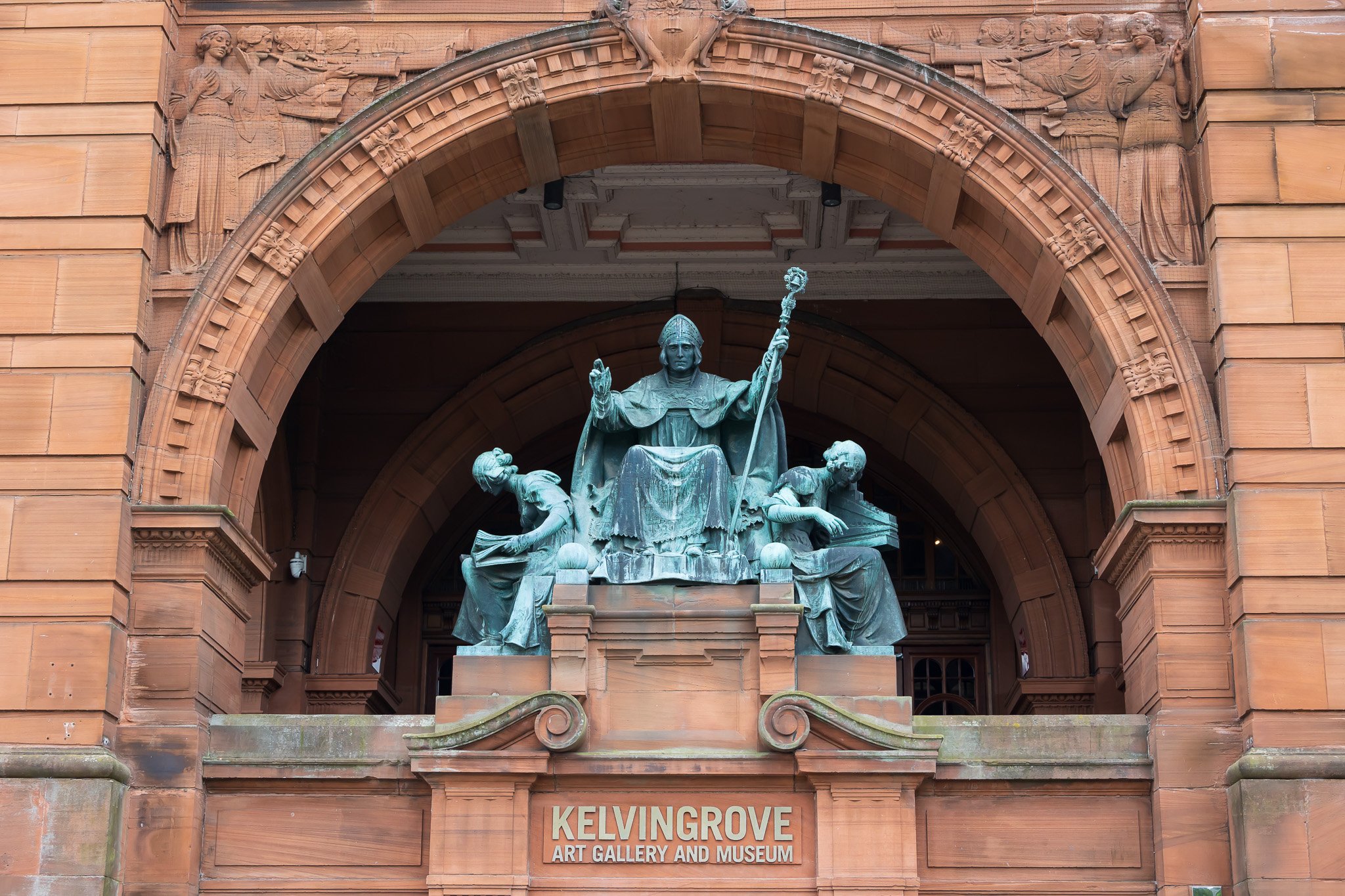

The majority of the structures and pavilions were temporary. When the exhibition closed, the remaining buildings were the Sunlightcottages and the Fine Arts building, now the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum.

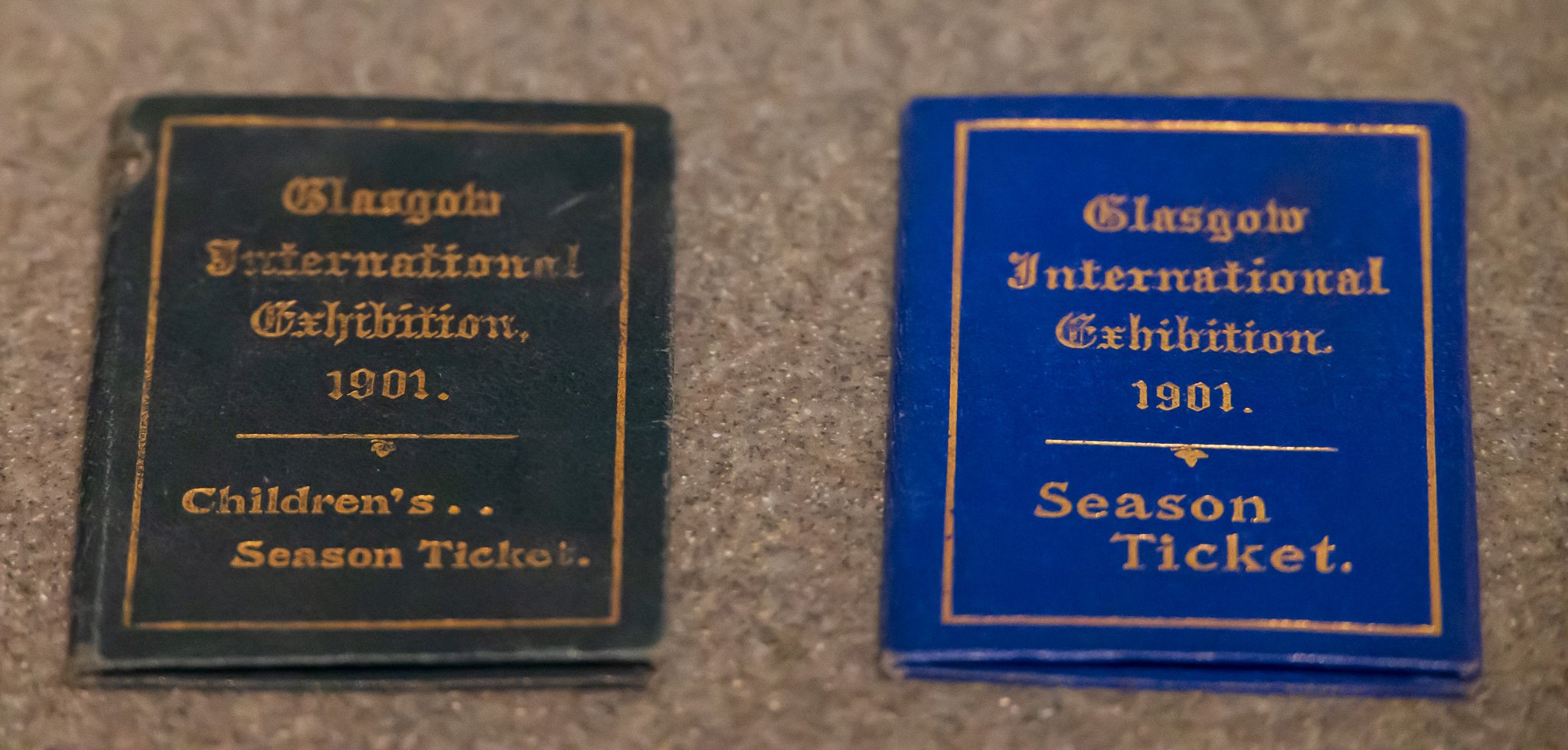

The museum’s art collection includes taxidermy, armour, a spitfire plane hanging in a hall, Salvador Dali’s painting Christ of St John of the Cross and my favourite, the Floating Heads installation. Perhaps less popular but more poignant for my visit was the collection of artifacts and images from the 1901 Exhibition. The collection includes original exhibition tickets, commemorative plates and photos of the Russian Village and pavilions.

Kelvingrove is an impressive museum with over 8000 objects and international art on display. It’s worth a visit if you are in Glasgow. But if I’m honest, dear reader, I would have rather visited with Karl and experienced gondola rides, water chutes, and world pavilions.

If you are new to the Karl Chronicles, get caught up on our expedition around the world! Start here with: 100 highlights from 100 Chronicles

Then get caught up on the rest of our journey, click here for more Karl Chronicles

The Karl Journey is now registered as an official expedition with the Royal Geographical Society