If we consider the major cities in Canada from the east coast to the west coast, the City of Winnipeg is almost smack dab in the middle. Although not the exact longitudinal centre — that distinction belongs to Tache, Manitoba, about 30 minutes east of Winnipeg— it’s close enough.

When Karl arrived here in Winnipeg, it was a time of economic prosperity in part due to the arrival of the railway. But, as shared in Karl Chronicles #63, that railway was completed at the cost of 4000 lives of Chinese labourers. At that time, the human rights of those Chinese workers and expectations of safe working conditions would have been an unfamiliar concept. In fact, in the years following the Canadian Confederation, people were more concerned with freedom of speech, religion, and the press — those freedoms afforded primarily to white men.

But this central geographical spot in the heart of Canada was considered the most appropriate spot to develop a new museum. The Canadian Museum for Human Rights, located in Winnipeg, is the world’s first museum dedicated to exploring the subject of human rights. The museum's mandate is to promote respect for others, encourage reflection and dialogue, and serve as a positive force for change in the world.

The building was constructed at “The Forks”, the confluence of the Red River and Assiniboine River, also a National Historic Site as a significant ancestral location to the Indigenous people. The museum is designed symbolic of its subject content — a journey from darkness to light, a building of hope.

The building design highlights include:

Red tint and fabricated cracks on the ground floor in homage to the clay mud of the Red River,

Criss-crossing ramps between galleries upwards for 800 metres along black concrete walls,

More than 1,300 panes of glass designed to look like the folded wings of a dove wrap around the museum, and

The " Tower of Hope ". A glass tower, rising 100 metres—dedicated to the museum’s visionary, the late philanthropist, Israel Asper.

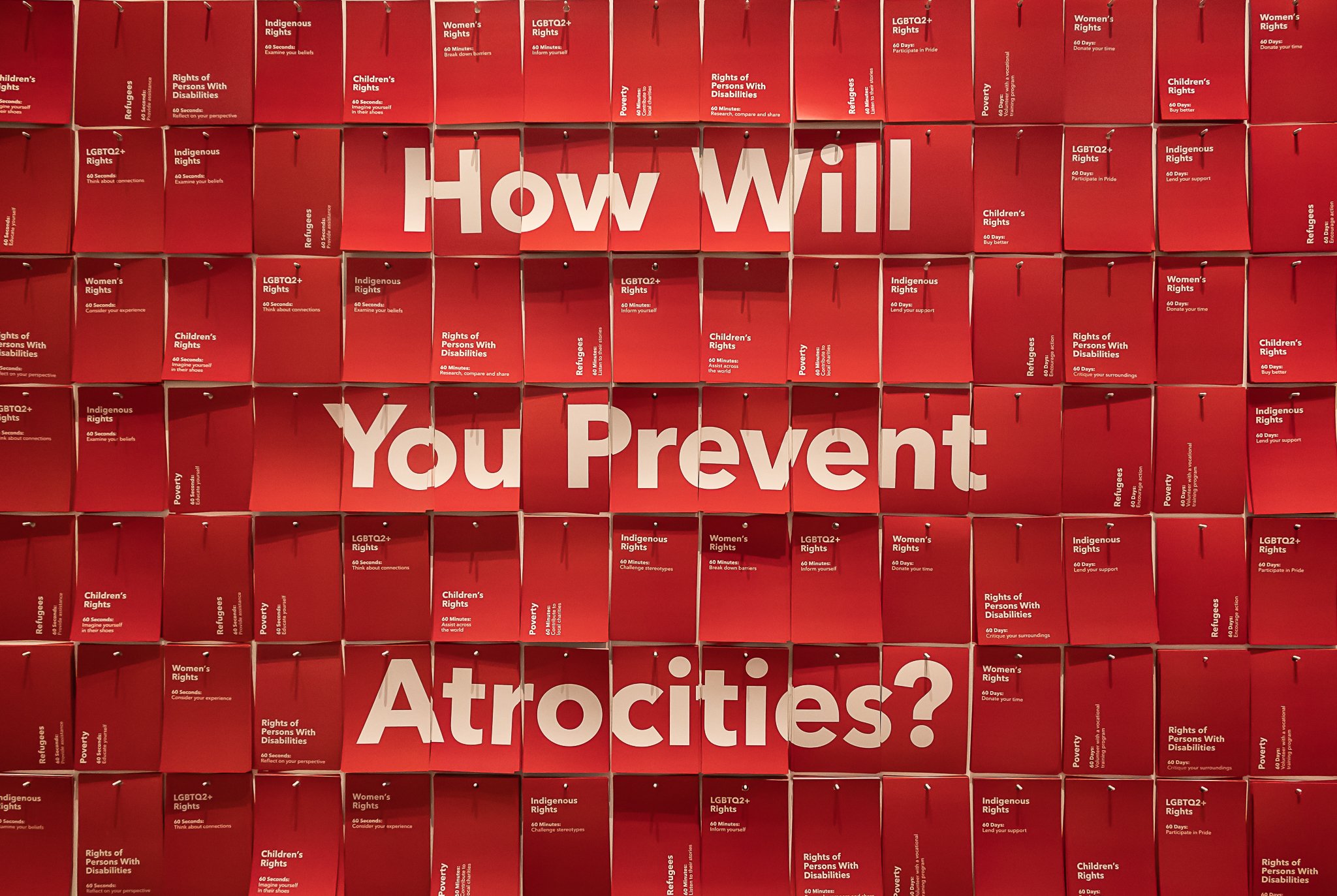

Inside the museum live the stories — interactive, visual content. A harsh reminder with every step in elevation to that Tower of Hope of how awful we can be as human beings.

Starting in the lower levels of the museum are some of the permanent exhibits depicting the most horrific violations of human rights:

Thousands of First Nations, Inuit and Métis children died from neglect and abuse throughout more than 100 schools that the churches established to remove children from the influence of their families and communities, language, culture, and beliefs.

The 8,300 Bosniak men and boys killed after the dissolution of Yugoslavia during the Srebrenica Genocide of the Bosnian War.

The mass sexual violence committed against Tutsi women and girls and more than 800,000 Tutsi killed in Rwanda.

The Holodomor famine-genocide of 1932–33 at the hands of Josef Stalin, who engineered a food shortage in Soviet Ukraine. His goal was to destroy Ukrainian ambitions for independence and ensure Ukrainian subservience to the Soviet state. As a result, millions of Ukrainians experienced the extended suffering of desperate hunger and died. Note, dear reader, the irony of writing this and the recent invasion of Ukraine makes that “Tower of Hope” feel even farther out of reach.

But, as you walk up to higher elevations on the ramps, the exhibits start to depict struggles and successes related to women’s rights, economic rights and political rights:

Struggles for gender equality with the story of five women fought to change the definition of the word “Persons” under the British North America Act, which referred only to men.

In Manitoba, Nellie McClung was instrumental in getting the first Province in Canada to allow women to vote in 1916.

The Miners in Elliot Lake, Ontario, suspected there were links between mining uranium and the high incidences of lung cancer and silicosis. Their concerns led to a royal commission on mine health and safety, creating the first Occupational Health and Safety Act in 1978.

And as the ramps move higher, there are glimpses of light — hope. There is an exploration of contemporary and historical human rights stories in the exhibits on the upper levels, Canada and worldwide. Such as the impact of movies and television like Star Trek on human rights issues related to perspectives on war, class and racism.

There is a beautiful quote at the museum from Eleanor Roosevelt, the First Chairperson of the United Nations Commission on Human Rights: “Where, after all, do universal human rights begin? In small places, close to home — so close and so small that they cannot be seen on any maps of the world.”

The purpose of the Human Rights Museum seems more critical than ever before in our world, where we seem to confuse the concepts of human rights and discrimination with that of personal restrictions. I recommend everyone passing through Winnipeg pay a visit to this museum to learn more of these stories and our respective roles in supporting human rights and furthering the conversation at home and abroad.

In case you’ve missed them, click here for more Karl Chronicles